Just how dysfunctional is this Congress?

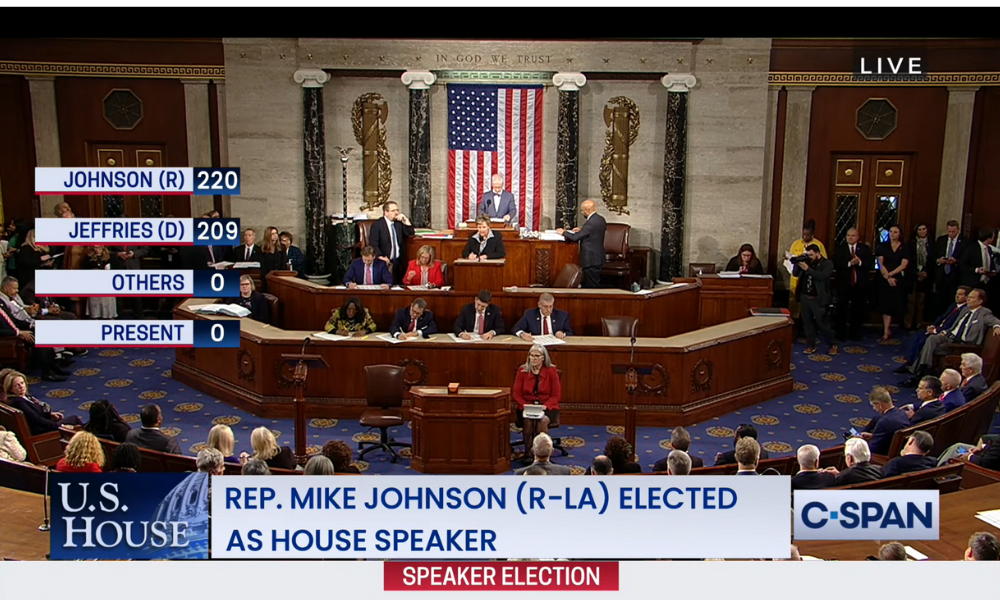

After three weeks of infighting, the U.S. House of Representatives finally has a speaker. Republicans, who hold the House majority, elected Rep. Mike Johnson of Louisiana, a lesser-known, more conservative member of the GOP.

If this feels like deja vu, that’s because Republicans were similarly deadlocked over who should be speaker back in January. Rep. Kevin McCarthy of California ultimately secured the gavel, but he was ousted after just nine months. The speakership battle is the latest example of dysfunction in Congress, which barely avoided a government shutdown in September.

To put the political stalemate in historical context, we turn to Jeffery A. Jenkins, Provost Professor of Public Policy, Political Science and Law for the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy. Jenkins literally wrote the book on contested speakership elections, co-authoring Fighting for the Speakership: The House and the Rise of Party Government. He recently updated the book following the January speakership battle.

In historic terms, just how dysfunctional is the current House?

We haven’t seen this kind of dysfunction since the Antebellum Era – before the Civil War. Between 1849 and 1859, we saw three speakership battles go 44 ballots (two months), 63 votes (three weeks), and 133 ballots (two months). Looking back, we can see that the nation was melting down over slavery, and these three speakership elections were “canaries in the coal mine.”

Beginning in the mid-1860s, all of that dysfunction was put aside. The parties figured out a way to deal with internal difficulties internally. And when they acted publicly, like on a House speakership vote, they held together.

Why have we gotten to this point?

The problems the Republicans are facing have been building for some time. Over the last ten years, speakership candidates have seen an increasing number of defections. It used to be the case that if you voted against the party’s speakership nominee, you were committing a “cardinal sin” as a party member. But those party norms have fallen away in recent years.

In my book, I discuss the majority party in the House acting like an “organization cartel” – a group that organizes the chamber with certainty at the beginning of a Congress. That organizational cartel arrangement had held together for over 150 years. But there have been changes internal and external to Congress in recent years — leading to the diminishment of committees, the limiting of amendment opportunities, and the weakening of party leaders’ control over members — that have put the organizational cartel at risk.

What was it about Johnson that got him elected Speaker?

He is on the more conservative end of the Conference, so the Freedom Caucus members and MAGA types supported him. The more moderate members of the GOP – those who are more “establishment” in their mindset – also decided to support him. Maybe they got worn down over the last three weeks and simply chose to end things. Johnson wasn’t a terribly well-known member of the Conference; while he’s very conservative, he doesn’t have a reputation for being acerbic or a “bomb thrower.” Maybe they simply needed to settle on someone who the far right could support and the rest of the Conference didn’t have strong feelings about.

The resolution of this speakership election reminds me of the one in 1859-1860 (the 36th Congress). That took two months to conclude, and the way that it was done was to remove the popular Republican nominee, John Sherman, and replace him with, effectively, a non-entity: William Pennington. Pennington was a freshman House member and wholly unknown, and this seemed to do the trick. Enough dissident members – who wouldn’t support Sherman – moved to Pennington and elected him

Will he be an extreme-conservative as Speaker?

Hard to say. His initial statements were somewhat mild – he wants to decentralize power in the chamber, away from his newly-elected office and toward the members. He also supports a bipartisan committee to study the debt issue and wants to immediately help Israel in whatever way they need.

We forget that Nancy Pelosi, as a regular member, was pretty extreme in a liberal direction. And then when she became Speaker, she put the needs of the whole Democratic Caucus ahead of her own viewpoints. Perhaps Johnson will do the same. The median member of the Republican Conference is not as conservative (across the range of issues) as he is.

What are the long term ramifications of this dysfunction? Was this a one-off or are we in for more of the same?

I don’t see any way the Republicans can have a House majority in the near future without the MAGA Republicans in the conference maintaining their pivotal status. If Republicans hold onto their majority, it likely won’t be larger and the number of MAGA Republicans will likely increase.

If the Democrats return to the majority, they’ve shown the ability to hold together better than the Republicans. The most extreme part of the Democratic Party – the strong progressives and the “Squad” – haven’t been as problematic as the extreme part of the Republican Party. The difference is this: the extreme Democrats generally want what the majority of the party wants in terms of policy, they just want more (or more extreme versions) of it.

The extreme Republicans essentially dismiss normal governing. They don’t want more policy. They want to upend our notion of what the federal government is about. They are willing to take us off the cliff to get it.