USC Schaeffer webinar spotlights increase in deaths of despair among those without BA

By Matthew Kredell

Even before COVID-19, an epidemic was sweeping the U.S. and contributing to the country’s first three-year drop in U.S. life expectancy since the Spanish flu.

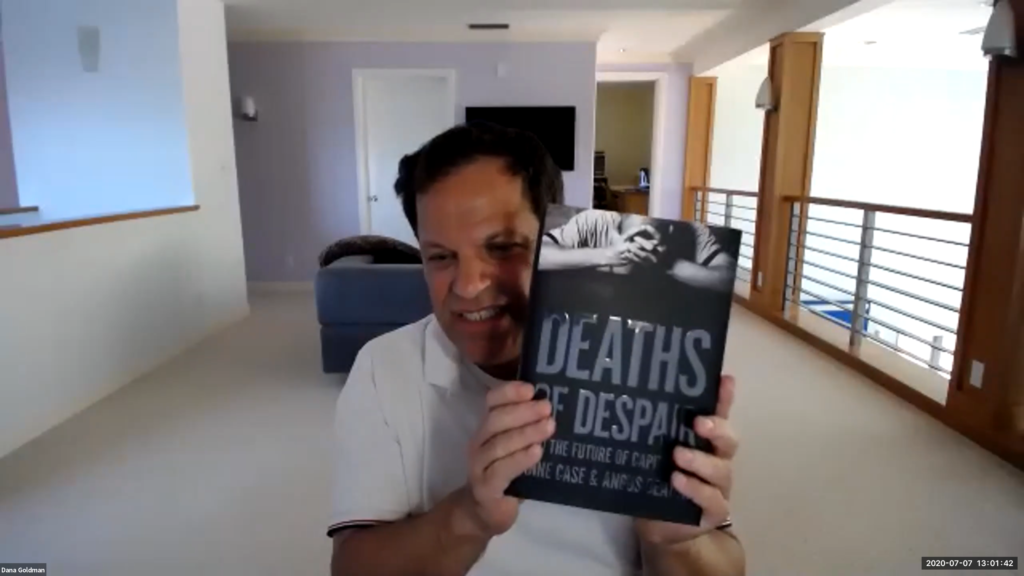

Dana Goldman, interim dean at USC Price and director of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, moderated a USC Schaeffer discussion July 7 that took a look at the rise of deaths of despair from suicide, drug overdose and alcohol abuse over the past two decades, and how today’s pandemic has further exacerbated the matter.

Goldman spoke with Nobel laureate Sir Angus Deaton, a distinguished fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center, and Professor Anne Case, his co-author for the book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism.

Case said they became interested in the topic when they realized that mortality rates among middle-aged white people in the U.S. began to rise in the late 1990s.

They noticed the major cause seemed to be a rise in suicides, drug overdoses and alcohol-related liver disease. In 2018, there were 158,000 deaths in the U.S. from those causes.

In looking at those numbers since 1995, the authors found they were strikingly higher among people without a bachelor’s degree. There were also increased self-reports of poor mental health and pain among those with less than a four-year college degree. The increases were almost identical among men and women.

“It’s very expensive to go to a state university, when in the past it would have been an easy way to put your toe in the water at a low cost,” Case said. “These state universities now cost almost as much as going to a private school.”

While the mortality rate of African Americans and Hispanics hasn’t seen the same increases, the authors found a similar disparity in deaths of despair based on a college degree in the African American community as well.

The root of this despair seemed to be the long-term labor market decline that began in the 1970s.

While countries around the world have experienced similar changes in labor market dynamics, Case and Deaton point to two factors that make the U.S. uniquely susceptible: the opioid crisis and the U.S. health care system, which is the most expensive in the world.

Case added that she doesn’t think the solution to the health-outcome divide is to get everyone a bachelor’s degree.

“We think people should have the kind of training they can get in some European countries, and there should be a status associated with having certain skills and certificates,” Case said. “You should be able to live middle-class lives with those skills. So we’re not out there trying to sign everyone up for a four-year degree, but we want to be able to spread the wealth to people without.”

Deaton pointed out concerns that social distancing is further widening the gap between those with an advanced degree and those without.

“The educated elite stay at home, peer into our computers, appear on zoom, go on working and get paid,” Deaton said. “This lower-educated group is going to lose out on life expectancy and lose out on income, so the mortality differential across these groups is surely going to widen.”

It’s estimated that 27 million people in the U.S. have lost their health insurance as a result of losing their jobs to COVID-19. Most European countries have a system that doesn’t tie health insurance to employment.

Deaton asserted that a silver lining that could come out of the COVID-19 crisis is health care reform.

“The health care system will change because of COVID,” Deaton said. “We need to get away from this monster that’s eating the economy alive, generating most of the federal deficit, stopping people from getting educated, destroying jobs in the labor market and delivering really bad health.”

Related faculty

Dana Goldman

University Professor of Public Policy, Pharmacy, and Economics

Leonard D. Schaeffer Director of the USC Schaeffer Institute for Public Policy & Government Service