By Cristy Lytal

For the first time in more than 30 years, reparations-focused House Resolution (H.R.) 40 has cleared the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary and is heading to the floor for a full vote.

First introduced in Congress in 1989 by the late Representative John Conyers and reintroduced every year since, H.R. 40 is named for the “40 acres and a mule” that were promised in 1865 but never delivered to the Americans emancipated from slavery in America. The bill proposes a commission to study slavery and discrimination in the colonies and the U.S. from 1619 to the present, and to develop reparations proposals for African Americans.

“People did not receive any benefit from their labor – that’s hundreds of years of slavery, and the fact that you worked for somebody else to build their wealth,” said Professor LaVonna B. Lewis, the Associate Dean of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

“And then, when there are multiple opportunities to make a decision to support Black involvement in the economy, there was always push back – the first being the 40 acres and a mule, which never happened. And when we were promised 40 acres, white Americans were promised 160 acres, and they actually got them.”

Dr. Lewis’ summary only hints at the very beginning of a long history of discriminatory policies and unfair implementations that contributed to what is now an eight-fold wealth gap between the typical white and Black household, according to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances.

A foundation of legislation that missed the mark

Some may not realize that one of the most paradigm-shifting pieces of U.S. legislation, the original Social Security Act signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, did not provide a safety net for everyone.

In fact, “the decision is made that yes, we want social security, but not for agricultural workers or for domestics – jobs that were disproportionately held by Black people at the time,” said Lewis.

Two other game-changing pieces of legislation followed that created the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) to offer mortgage insurance and facilitate homeownership, and the GI Bill to provide low-cost VA home loans to World War II veterans.

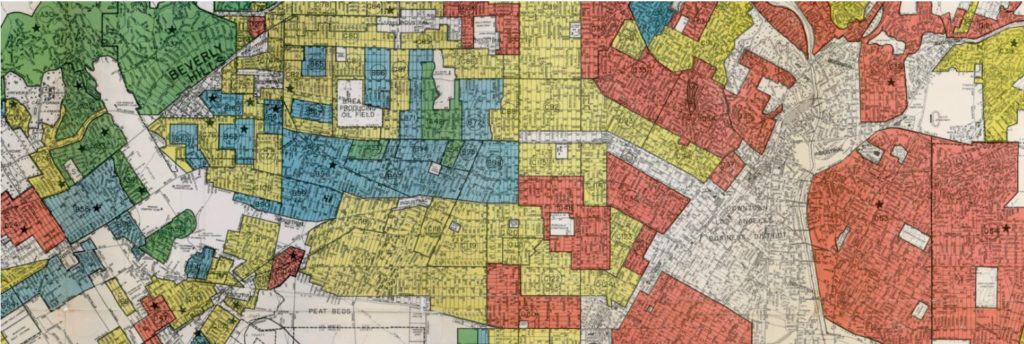

However, these FHA-backed loans and VA loans were routinely denied to Black citizens and veterans through a variety of racist tactics, including deed covenants in many neighborhoods that banned the sale of property to people of color, and mortgage lenders or banks that often “redlined” neighborhoods that contained any Black household by refusing or limiting loans, offering bad rates, and more.

“Black veterans did not have access to the same benefits that white veterans coming home from World War II did,” said Professor Richard K. Green, Director and Chair of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate. He makes plain the injustice of this inequity. “These veterans were just as shot at by the Nazis and the Japanese as their white peers were. In fact, they sometimes were the first wave.”

Another instrument that widened the racial wealth gap was eminent domain, which the government often abused to forcibly purchase Black-owned properties for far less than market value.

One local example recently made headlines: in 1924, Manhattan Beach officials used eminent domain to forcibly purchase a Black-owned resort for far less than its market value, claiming they needed the land for a public park but then failing to develop it for three decades. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted 5-0 to return the land—worth approximately $75 million—to the family’s living relatives.

“There’s been this systematic method of expropriating property from Black folks disproportionately,” said Green.

When President Dwight D. Eisenhower passed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, this created even more occasions for the government to expropriate Black-owned businesses and residences in order to make way for the Interstate Highway System.

A multifaceted case for reparations

In more recent years, the wealth gap has continued to widen, compounded by everything from racist lending practices in the years leading up to the subprime mortgage crisis and Great Recession, to the host of iniquities playing out during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s a compelling case that the only way to actually achieve equality in the United States for Black families is that you need to provide restitution for what had been stolen from the generations of those families over time,” said Professor Gary Painter, Chair of the Department of Public Policy and Director of the Sol Price Center for Social Innovation. “And in some sense, there really is no other remedy for the Black/white wealth gap other than reparations.”

At a recent USC Price seminar moderated by Dr. Lewis, authors William Darity Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen discussed four key recommendations from their book From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century.

First, Darity and Mullen emphasize that those eligible for reparations need to establish their identity and lineage: they must have self-identified as “Black, Negro, African American or Afro-American” for the last 12 years, and have at least one ancestor who was enslaved in the U.S.

Second, reparations need to eliminate the wealth gap between Black and white Americans.

“The racial wealth gap amounts to a condition in which the average Black household in the United States has approximately $840,000 less in net worth than the average white household,” said Darity, a professor at Duke University.

“It has resulted in a situation that corresponds to a circumstance where Black Americans, who have ancestors who were enslaved in the United States and who were denied the 40 acres that were promised in the aftermath of the Civil War, constitute about 12% of the nation’s population, but only possess less than 2% of the nation’s wealth.”

Third, the payments from reparations need to be delivered to eligible recipients as direct transfers.

“This may or may not mean that these are cash transfers,” said Darity. “But we think it’s absolutely essential that the individual recipients have discretion over the use of the funds” — which was the case with reparations payments given to victims of the Holocaust, the Japanese internment, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Boston Marathon bombing, and the Iran hostage crisis.

Last, reparations need to be the responsibility of the federal government rather than the states. This is because the current racial wealth gap is largely the consequence of federal policies and notably, because the estimated $11 trillion needed for reparations far exceeds the total budgetary capacity of all U.S. states combined.

Public opinion wavers with limited support

Even though H.R. 40 just seeks to study slavery and discrimination, and develop proposals for reparations, it isn’t likely to pass both houses of Congress. Only 20% of Americans support reparations, according to a 2020 poll conducted by Reuters/Ipsos.

Even so, it’s important to continue the discussion. “The fact that it made it out of the House Committee on the Judiciary is an extension of the conversation that we started with George Floyd’s death,” said Lewis. “One can see that there are pockets of the public that are already tired of the conversation … that there are people that don’t want us talking about these issues, because it makes them sad or it makes them uncomfortable.”

Green theorizes that the low rate of support is partly due to the fact that Americans are out of touch with their nation’s history.

“I think slavery has become an abstraction,” he said. “People don’t relate to it. They should, but they don’t. People can’t imagine what it would be like to be enslaved. They think in the abstract ‘Oh God, that was horrible,’ but they don’t feel it.”

According to Painter, Americans lack awareness not only of slavery, segregation, and discriminatory practices and policies that have disadvantaged Black citizens, but also of policies that have increased white people’s intergenerational wealth.

“[White Americans] don’t imagine ourselves as beneficiaries of those policies, because they happened to our grandparents or our great-grandparents,” he said. “And so that’s why reparations is a politically challenging policy to advance, because current people have trouble understanding the huge advantages they have for things that they didn’t actually experience themselves.”

Mullen lays part of the blame on textbooks and historic landmarks that frame a false narrative of the Confederacy as a romantic lost cause to preserve states’ rights, rather than as an act of traitorship to maintain slavery. This is evident in everything from plantations that now function as wedding venues, to statues that represent Confederate generals as heroes.

“One of the things we talk about in From Here to Equality is the need for a national education campaign,” said Mullen, who is a folklorist and the founder of Artefactual and Carolina Circuit Writers. “In conversation after conversation, we’re learning that Americans don’t know our history, and it’s not our fault entirely. The textbooks that many of us were exposed to were textbooks that were commissioned by groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the American Daughters of the Republic.”

The outcome of our discussions on reparations has yet to be determined, and to say that these discussions are contentious is to state the obvious. Nevertheless, there remains a moral imperative to make good—or at least better—on the original promise of post-enslavement equality in the United States.

“We didn’t get on this path because we thought reparations would immediately occur,” said Darity. “I mean, reparations hasn’t taken place for 156 years. But we got on this path because we’re absolutely convinced that this is the right thing to do from the standpoint of the health and wellbeing of American society, as well as the health and wellbeing of Black America.”Watch the full event “From Here to Equality: A Conversation on Reparations for Black Americans” at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jnqPOUcPEc8