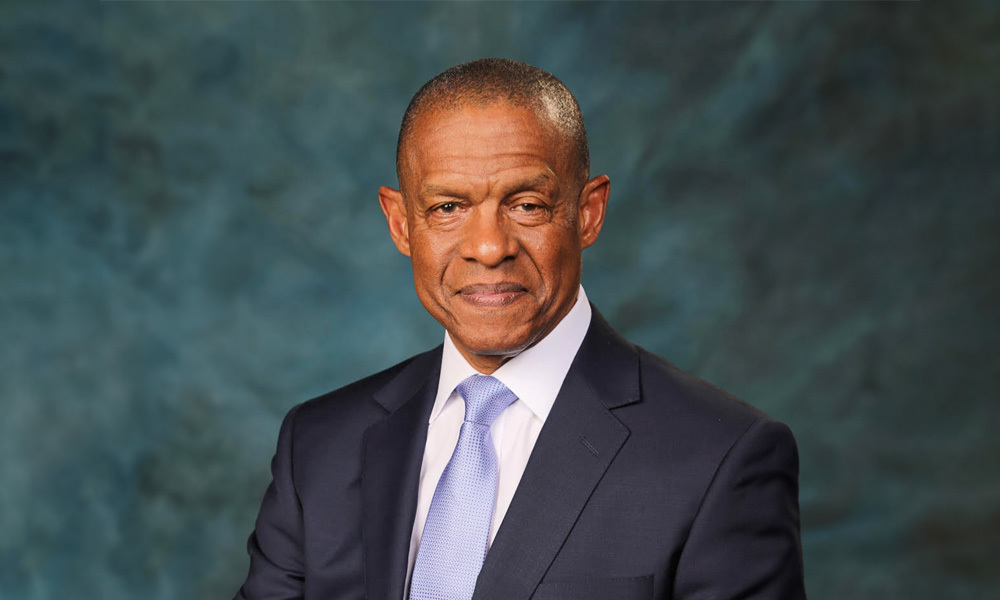

The Los Angeles Police Commission recently elected Erroll G. Southers as its next president, putting the USC professor and former FBI agent in charge of the body that oversees one of the nation’s largest police agencies.

Southers, professor of the Practice in National and Homeland Security at the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy, will now set the agenda for the civilian panel, which functions much like a board of governors for the police department. Southers also serves as associate senior vice president of Safety and Risk Assurance at USC.

We caught up with Southers to discuss his goals for LAPD and some of the complex public safety challenges facing Los Angeles, from boosting transparency to recruiting more officers.

Why did you take this job?

I have had a more than 40-year relationship with LAPD, even though I never worked for them. I’ve also had a 15-plus-year relationship with Mayor [Karen] Bass, who is a USC alum. She’s been a mentor throughout my career and I was honored when she asked me to consider an appointment to the commission.

I can’t tell you how many LAPD officers have been my students. In addition to the experience I’ve had in law enforcement, I actually know these people. I think I will have a tremendous opportunity to examine the department’s transparency and accountability, and if I am critical, officers will view it as coming from someone who understands what they do.

Where could LAPD use more transparency?

Some of the adjudication outcomes – such as officers being terminated, officers being disciplined with days off – are outcomes that cannot be shared. Because of that, the public believes nothing’s happening. I can tell you as someone who sits in those meetings, when those incidents are adjudicated, that is the furthest thing from the truth.

Master of Public Administration Online

Advance Vital Institutions

Advance your career and the institutions you serve with our exceptional MPA online.

Find Out MoreUse of force investigations involve tens if not hundreds of hours of investigative work consisting of interviews, statements, photographs, drawings, videos, and forensic evidence. If the public knew that’s what we’re reviewing, I believe they’d have a greater level of trust, and we need to do a better job of sharing the process with the community.

How can LAPD replenish its depleted staffing ranks?

It’s a real challenge. You’ve got people today that quite frankly may not want to be police officers. We have people who want to work remotely, on a reduced work schedule, or a hybrid work schedule. In this profession, you have to come to work.

Of course, there’s an image challenge right now after the death of George Floyd and other similar incidents, which makes it particularly difficult to recruit. We are also trying to achieve compensation parity with other agencies as it relates to pay and benefits. It’s a very competitive environment for a very selective profession.

What also makes this challenging are the standards that we set. For every 100 people who apply, we may hire less than 10. This is a profession that cannot compromise on the standards because it involves the safety and security of the community.

What are some police reforms to consider?

The toughest thing now, in terms of reform, is making sure we select the right people for the job. We are considering an applicant pool that is not comprised of perfect people. It’s called the human race. Understandably, regardless of our recruitment and vetting process, there are some candidates who may successfully complete the process but should not be police officers. If officers have to leave the profession due to misconduct, they need to leave for good. Knowing that fact should enhance public trust.

I’ve always attempted to support police officers to the extent reasonably possible. But when they’ve crossed that line, and it’s resulted in being terminated, I feel just as strongly that those individuals should move on to a new profession. They’ve broken that trust, and it’s done.

How can LAPD improve community relations?

One thing that I see as a challenge is misinformation. For example, there are people who still believe that canines, meaning our dogs, are trained to find and bite. They haven’t done that in decades.

It means being more aggressive in terms of marketing the things that the department is doing well. Almost every week I listen to reports and presentations about some tremendous programs that are going on in LAPD with the community where they’re working together, and no one ever hears about it.

How can LAPD help improve officer mental health?

We’ve had two officers take their lives recently at LAPD. It is tragic and a national challenge. Many officers believe no one likes them. No one cares about them. In addition, they see things every single day that the average person will never see in their lifetime. That takes a toll.

We have to do everything possible to ensure officers know that help is available, and tell them to seek that help. Most importantly, it’s not penalizing them for doing that. Years ago, officers were of the belief that if they seek help, they’re going to be seen as weak and not get promoted. That’s the furthest thing from the truth. Now, no one holds that against an officer when it comes time for promotions or advancement. Hopefully, if they do seek help, we can retain them throughout their career in a very healthy mental state.

Officer wellness has to be the highest priority; without them we will never accomplish the community safety goals we desire.