By Eric Ruble

Income inequality is at an all-time high in the United States, and recent research suggests it could impact how much money charities receive. A study co-authored by USC Price School of Public Policy Associate Professor Nicolas Duquette shows that in a controlled environment, people are less likely to donate to a charitable cause when wealth disparity is greater.

“There has been a radical shift in the distribution not just of wealth but also in the distribution of giving and philanthropy that has definitely influenced the way charities operate. But we don’t necessarily recognize this big shift in our civil society,” Duquette said.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the top 10% of earners own 76% of the country’s wealth, while the bottom 50% own just 1%. In 1989, those figures were 66% and 3%, respectively. The problem is even worse when race is considered; the Fed says 75% of Black families and 67% of Hispanic families are in the bottom half of wealth distribution, compared to 41% of white families.

A basic experiment with wide-reaching applications

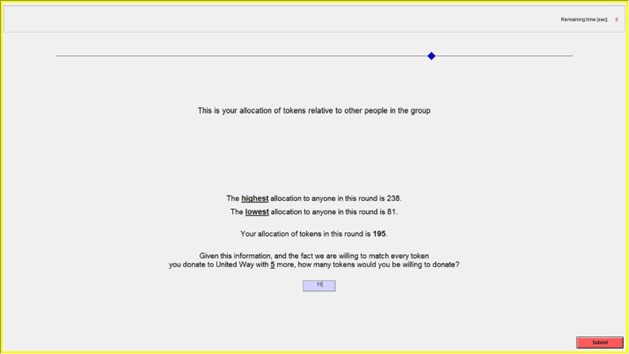

Duquette and his co-author, Professor Enda Hargaden at the University of Tennessee’s Haslam College of Business, conducted a relatively simple experiment: they gave college students varying amounts of real money and told them they could take it home, donate it to the United Way, or a combination. Critically, the students were informed of how much they were given (denoted as “tokens”) compared to what other students received.

“They were able to see how much money they had for this decision, how much money other people had, and how inequitable that distribution was,” Duquette said of the study, which was published in April 2021. “We followed a pretty standard economic experience practice where we gave them a decision to make and observed what they did when we changed the terms of that decision.”

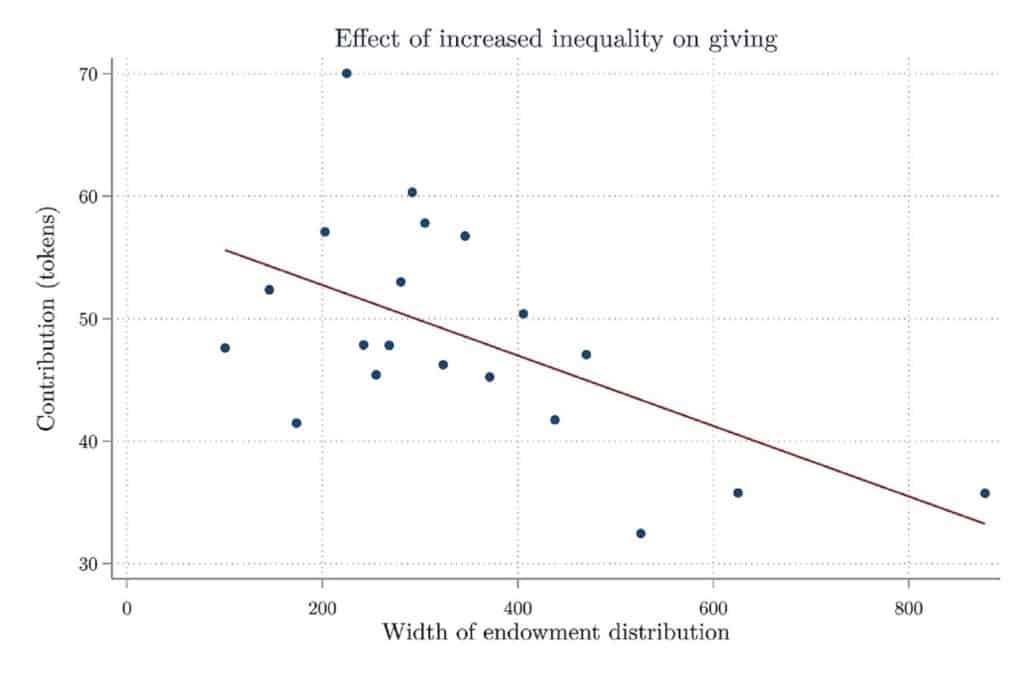

The laboratory-based study found that as the difference grew between those with the most and fewest tokens, participants donated less.

“Even that little bit of inequality, that didn’t really matter, led them to change their giving behavior,” Duquette said.

An example of what participants saw when participating in the study.

Duquette has extensive experience studying the behavior of nonprofit organizations, and has recently co-published several papers about charitable giving. He noted that in this experiment, it is still unclear whether the decline in donations amid greater inequality is directly due to that disparity, or if it is because of broader social changes.

Still, he said the results challenged his thinking.

A graph showing how donations decreased as wealth disparity increased.

“I was surprised by the fact that people’s behavior does seem to change when inequality changes. That really ran counter to the way that I tend to think about both human behavior and about inequality,” he said.

Duquette remarked on how his findings add to existing conversations on inequality, especially if the pattern of wealthy individuals donating less when the wealth gap is larger holds true at a large scale.

“Our findings made me take more seriously people who are upset about inequality for its own sake, not just that it’s a sign of deeper structural problems in the economy, but that to them inequality is inherently objectionable.”

Implications for the real world

The research produced useful findings for charitable organizations. Most notably, it suggests they will likely be focusing more fundraising attention on a small group of donors who give in large amounts instead of a larger group of people who donate in smaller quantities.

“[Organizations] are getting more and more dependent on the major donors who can write big checks,” Duquette said.

Through a wider, societal lens, Duquette believes the research demonstrates the degree to which wealth disparity influences how people spend their money.

“Looking at the distribution of resources in our society affects the way that people view others and their own willingness to help each other,” he said. “What we think we’re seeing is that social inequality is actually leading to different economic decisions about how to support civil society.”

Moving forward, Duquette said he and Hargaden would like to conduct more experiments about the perceptions of inequality and how they affect other behaviors. They also want to examine how these perceptions and behaviors have changed over time.

“I think that’s really how you can see the effect of multi-decade shifts and social structures, and the distribution of resources,” he said.

In the political sphere, the research can provide policymakers with guidance for making decisions about laws impacting charitable organizations and other nonprofits. Duquette said that when people donate to charity, they are in a completely different mindset than when they are making purchases for themselves, and leaders should acknowledge that.

“It’s not just a consumer decision. It’s a social action. We need to be mindful of that when we set policies to nurture our charities,” Duquette said. Those policies may help determine the degree to which charities succeed. With guidance from Duquette and other researchers, people in power can ensure organizations helping those most in need are able to fulfill their missions, even if the wealth gap continues to grow.