By: Eric Ruble

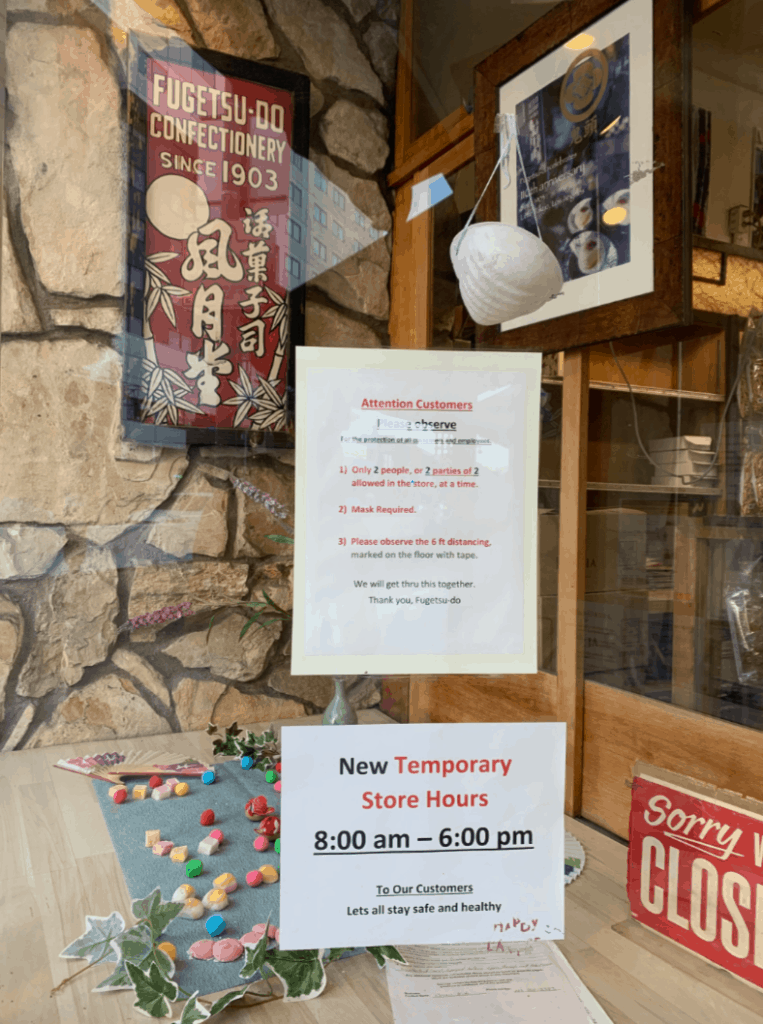

Since the start of the pandemic, small businesses nationwide have been closing their doors for good. These stores and restaurants aren’t just part of our neighborhoods’ economic lifeblood – they’re often cultural institutions.

USC Price Associate Professor Annette Kim and her students are on the frontlines of the effort to preserve and protect “legacy businesses” in Los Angeles that have served as landmarks for generations.

Each year, Kim’s students in her Urban Spatial Ethnography and Critical Cartography course work with local organizations to gather data on urban spaces, provide insights and present them in a visually digestible form. Kim, director of the Spatial Analysis Lab (SLAB) and founder of the Race, Arts and Placemaking (RAP) initiative at USC Price, encourages students to be creative and weave a narrative through their project that data alone cannot describe.

“The stories we tell and how well we communicate and emotionally connect with people is key. And as we’ve been seeing in our politics, straight data — facts — is not enough,” Kim said.

Spotlight on Little Tokyo

In the most recent course, four of Kim’s students focused on Little Tokyo. Master of Urban Planning candidate Lindsay Mulcahy interviewed long-term store owners about how the pandemic exacerbated longstanding issues in the community.

“I saw this as a really great intersection of how we support intangible heritage and cultural expression and how that can be rooted in place and policy,” Mulcahy said.

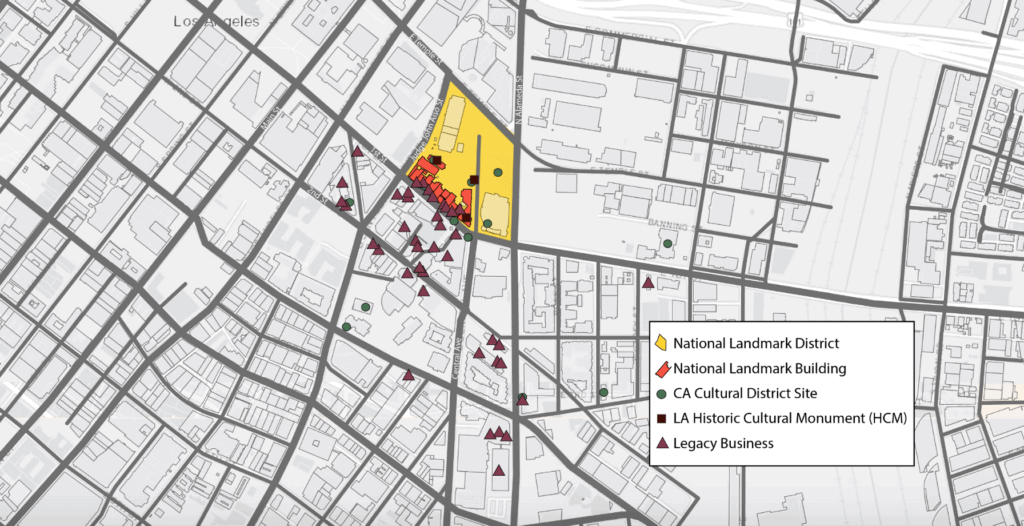

Her project, dubbed “Beyond the Plaque,” takes the “cartography” portion of the course’s title to heart; it literally maps out the locations of legacy businesses and denotes which buildings have protection status at the city, state and federal levels.

“One thing that Annette has really impressed upon me that’s going to stick with me forever is that whoever controls land controls everything. The fight for land ownership and land control is really tied to self-determination and cultural expression,” Mulcahy said.

As Mulcahy indicates in her project, the pandemic is just the latest in a string of challenges Little Tokyo businesses have faced since the neighborhood’s inception more than 130 years ago. Chief among them during the last decade: rising rents forcing small businesses to relocate from Little Tokyo’s dense core while large, corporate brands have established a presence.

It’s a problem with which Mike Okamura (USC ‘83), president of the Little Tokyo Historical Society, is intimately familiar.

“Small businesses — they really have to work hard at it and attract customers,” said Okamura, noting that before the pandemic, some businesses did not even have websites.

Stores and restaurants struggling to draw in customers received support from the Little Tokyo Service Center, which helped businesses secure Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans and promote their companies online.

“Little Tokyo Service Center provided young volunteers for almost all the small businesses to help them form a new business model so that they could at least try to stay afloat during the hardest time of the pandemic,” Okamura said.

Mulcahy proposes that Little Tokyo businesses receive assistance through rent cancellation, asserts that Los Angeles City Hall can take further action by establishing a grant program for legacy businesses – such initiatives have already been implemented in San Francisco and Austin, Texas, and proposed in Los Angeles – and emphasized the importance of leveraging community members who want to help, specifically highlighting the Little Tokyo Impact Fund.

Different Institutions Face Similar Concerns

Other students in Kim’s class chose to focus on other cultural assets within Los Angeles with the partnership of community-based arts organizations 18th Street Arts Center and LA Commons. No matter the place, each group shared a common problem: “All of them are trying to deal with displacement,” Kim said.

One group of students focused on highlighting displacement among immigrant populations and communities of color in Santa Monica. Their work was included in the 18th Street Arts Center’s Culture Mapping 90404 initiative.

Sue Bell Yank, deputy director of the arts center, said that city planners initially used the map initiative when beginning work on a new improvement plan for the Pico neighborhood. Today, the project continues to grow, with solution-driven input from students like those in Kim’s class.

“Digging into the research and creating narratives around some of these places and people were really impactful,” Yank said. “Every year, the students find some new, interesting aspect to dig into. And I think it’s really driving our map forward in really productive ways.”

An appointed member of the Los Angeles City Planning Commission, Karen Mack, who founded LA Commons in 2000 and serves as its executive director, said meeting LA’s needs through the planning process is “one of the most powerful tools we have to bring quality of life to our neighborhoods.”

Mack said that like the Japanese American community in Little Tokyo, the African American community in Leimert Park is dealing with gentrification caused in part by expanding Metro lines.

“Working to mitigate that is a shared challenge,” Mack said.

This year, Kim’s students created videos for LA Commons’ “Found LA” program, an online showcase featuring local businesses and artists in neighborhoods across the city.

“To bring their knowledge as well as their energy to bear in the situations is always valuable. I’m really passionate about young people and their opportunity to make a difference at this moment in particular,” Mack said.

Moving forward, organizations alone cannot bear the burden of keeping small businesses — and the neighborhoods they support — alive.

Kim’s students and their work is just one small, local part of that puzzle; but every year, her class helps set dozens of future leaders on a path toward making real change.

As Okamura said, “We all have to work together so that these businesses can be sustainable and thrive again.”