Earlier this year, New Hampshire voters received a phone message that sounded like President Joe Biden, discouraging them to vote in the state’s primary election. The voice on the line, however, was not really Biden’s – it was a robocall created with artificial intelligence (AI) to deceptively mimic the president.

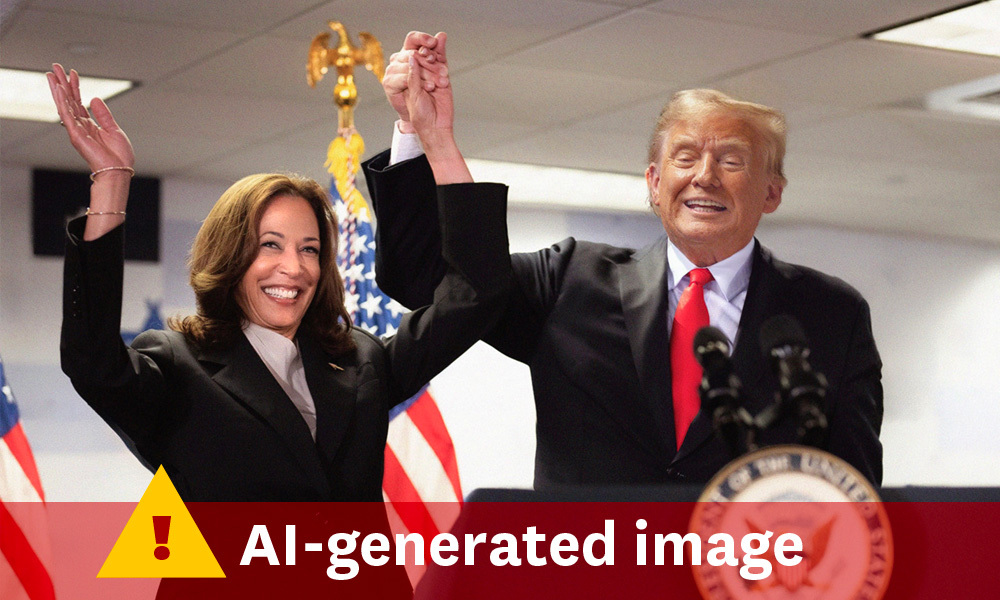

The rise of AI has made it easier than ever to create fake images, phony videos and doctored audio recordings that look and sound real. With an election fast approaching, the emerging technology threatens to flood the internet with disinformation, potentially shaping public opinion, trust and behavior in our democracy.

“Democracies depend on informed citizens and residents who participate as fully as possible and express their opinions and their needs through the ballot box,” said Mindy Romero, director of the Center for Inclusive Democracy (CID) at the USC Price School of Public Policy. “The concern is that decreasing trust levels in democratic institutions can interfere with electoral processes, foster instability, polarization, and can be a tool for foreign interference in politics.”

Romero recently hosted a webinar – titled Elections in the Age of AI – in which experts discussed how to identify AI-generated disinformation and how policymakers can regulate the emerging technology. The panel included David Evan Harris, Chancellor’s Public Scholar at UC Berkeley; Mekela Panditharatne, counsel for the Brennan Center’s Elections & Government Program; and Jonathan Mehta Stein, executive director of California Common Cause.

Here are some tips and policy proposals to combat AI-generated disinformation:

How to recognize and ignore disinformation

- Be skeptical. It’s not a bad thing to be skeptical of political news in general, Romero noted. If the news doesn’t seem quite right, if it’s sensationalized, or evokes strong emotions – that should be a red flag.

- Confirm across multiple sources. If you see an image or video that makes someone’s point too perfectly, confirms a conspiracy theory, or attacks a candidate – take a moment before sharing, Stein said.

“We are in an era in which instead of believing it, instead of retweeting it, instead of sharing it, you are going to have to go and double check it,” he said. “You’re going to have to Google it. See if it’s being reported by other sources. See if it’s been debunked.” - Use news from trusted sources. Consuming information from credible sources is one way to combat disinformation. People should also determine whether an article is news or opinion, Romero said.

“It can be hard for people to protect themselves against disinformation. It’s a lot of work,” Romero added. “Generally, the push in this field is to talk about how government and policymakers can take action to support communities.”

What policymakers can do

As U.S. policymakers try to tackle AI-generated disinformation, they could find inspiration from Europe. The European Union’s Digital Services Act requires tech companies with large online platforms to assess the possible risks their products pose to society, including to elections and democracy, Harris said.

“Then they have to propose risk mitigation measures and they have to get an independent auditor to come and audit their risk assessment plans and their risk mitigation plans,” Harris added. He noted the European law also requires tech firms to give independent researchers access to data to study how their products impact social issues, including democracy and elections.

In California, there have been dozens of bills attempting to regulate AI, according to Stein. One notable proposal would require generative AI companies to embed data within digital media that they create. That would let online users know which images, video and audio were AI-generated, when they were created and who made them. The bill would also require social media platforms to use that data to flag AI fakes.

Master of Public Policy

Advocate & Innovate for a More Just World

Effective public policy has the power to disentangle increasingly complex global and domestic challenges. With an MPP from USC, you will have that power too.

Find Out More“So, if you’re scrolling Twitter, Facebook or Instagram and something has been AI generated, under the bill, it would require that to carry a small tag somewhere that indicates it was AI generated,” Stein said.

At the federal level, there are bills in Congress that would regulate the use of AI in political ads and issue guidelines for local election offices pertaining to AI’s impact on election administration, cybersecurity and disinformation, Panditharatne said. The federal government has also published guidance on generative AI risk management, which includes information that could be relevant to election officials.

“But so far, we haven’t seen any sort of guidance that is specifically tailored to the use of AI by election administrators,” Panditharatne said. “So that is a gap, and it is one that is important to fill, in our view.”